Home and Native Land

What does it mean to make ourselves at home when the place we call home isn’t our native land?

I recently returned home to Austin after a two-week trip back home to Canada, my first since the start of the pandemic.

Just one sentence in and we’re already mired deep in questions. Where is home? Is home the land where we’re from, where we were born? Is home where we currently live? Is home the result of a choice, is home a divine assignment we receive at birth, or both? Can one ever truly feel at home when multiple places can claim the title of home?

I’ve lived in Central Texas for over 15 years now, a fact that feels unreal even as I type it. It’s home in the most functional sense: Austin is where I own a house; the house is where my family, my cat, and my stuff lives. It’s where my chosen people are, which is why I am still here.

I was born and raised on the south shore of Montréal, where my dad still lives in the house we had built in 1986 when I was 8 years old. This is home in the sense of provenance, of origin. This is the home that my cells recognize, where my body relaxes in a very specific way as it’s folded into the familiar landscapes of my childhood.

From 2000 to 2007, I lived in Victoria, British Columbia. This–the Pacific Northwest and its lush forests of Doug firs and Western red cedars–remains my spiritual home, the place I long for and ache to return to, the place that I knew in my bones was for me when I first landed there.

Texas never felt like that for me. When people ask me why I moved here, I always say, “For the only reason a sane person would move here: love.” My husband is from here, and we moved here two years into our marriage, for reasons that made lots of sense at the time, but which feel increasingly flimsier with each passing hellish year in the death cult that is the US in general, and Texas in particular.

This isn’t an essay about the aberrations that are Texas and US politics, although it could be. It’s an essay about plants, about climate, and about land.

This trip was the first I made back to Canada since 2019, which was the last time we made our annual pilgrimage to my homeland before the onset of the pandemic. Prior to travel screeching to a halt in 2020, we would travel to Canada every year, typically in August, for both of my parents’ birthdays.

The backyard of my childhood home is one of my very favorite places in the world. When we moved in in December of 1986, the yard was a square of flat dirt. Everything you see in the pictures below–the tall cedar edge, the grape arbor, the lush grass–was planted and tended to by hand by both my parents. I literally grew up with these plants; they signify home every bit as much as the house does.

When I am home, my whole system settles into the abundance of green. My eyes greedily drink it in: the broad-leafed trees, the grass, the abundance of flowering plants everywhere. I thrive in the cooler daytime temps, and my family and I like to spend as much time outside as possible, from morning well into the night.

Returning to Austin after these two-week, green-soaked interludes is always such a sharp, depressing contrast. Although I have come to expect it, the bleached-blond grass, dry and cracked soil, and desiccated gardens that await me upon my return still shock me with their stab of grief. Why do I live here again?

The first time I felt the sting of a heart being divided between two places was when I spent a summer in Jasper, Alberta, in the Canadian Rockies, way back in 1998. I had never spent an extended period of time away from home before, hadn’t fallen in love with a new landscape before. I knew from that summer that I’d forever be split, my heart belonging to multiple places, to multiple bioregions at once, while my body could ever only be in one place at a time.

This sense of split feels even keener this year. Returning home to Canada after three full years away (I’d never been away from home for more than a year before), having missed it dearly the whole time, gave a sharper edge to the feeling of belonging to the plants of home, knowing now that I could be kept away, that I couldn’t always choose to come back when I want to.

One night, in my mother’s backyard on the edge of a forest, communing with the trees and grass and (legal!) plant medicine, I had the profound realization that, for me, for humans, home is plants. Of course home is also people, is also a house, a neighborhood, a community. But I was forcefully struck with the truth of this, one that I have known for a long time in some way or other but that I could no longer ignore: I may have a house and people in Texas, but it doesn’t feel like home, because the plants don’t feel like home.

There are beautiful plants that I love in Texas. I have a deep relationship with the red cedar in our backyard: this tree holds me like an elder. I have begun to form a relationship with the cedar (really juniper) that grows wild in the region. I know that my favorite Texas native, the electrically grape candy-scented mountain laurel, blooms after the Texas redbud, and before the bluebonnets. I know I’m always sad to see the bluebonnets fade, but then remember that I actually prefer the red and yellow Mexican blanket that follows it.

I have come to know and love many plants here in Texas, but I don’t feel at home in this subtropical bioregion the way I feel at home in the temperate zone that encompass both my native home in the northeast, or my chosen spiritual home in the Pacific Northwest, because it’s oppressively hot and dry. When I moved here from Victoria, I tried to literally transplant my relationship with nature to my new southern home, but try hard as I could, it was never the same. For a long time, I thought the failure was mine, that I just needed to try harder to love this place. Now I know: it doesn’t feel like home because it just isn’t.

I’ve been sitting with these questions since I came back: what does it mean to make ourselves at home when the place we call home isn’t our native land?

My story is one of privilege: I’ve always been able to choose where I live, even though I might not make the same choices again.

I think of all of the Indigenous people, and people of the global majority, who have been forcefully displaced, exiled by colonization.

I think of everyone who has been, and will be, forced into relocation by war, and by climate change.

I think for how many of us have had, and will have, to make a home where we don’t feel at home.

I believe to root cause of trauma, for all humans, is the rupture in our relationship with the land: from the moment that our ancestors ceased to understand themselves as part of nature, and started the failed experiment of trying to dominate and contain nature, we have been exiled from our true home

After years of trauma work, both personal and professional, I have landed here: home is plants, and I am desperately trying to come home, and this is complicated by the fact that the bioregion where I currently reside feels inhospitable to me in a fundamental way.

How are we as a people going to learn to make a home with plants in a world that will be increasingly hot, dry, and hostile? How are we going to return home to ourselves as the plants that are our home become increasingly inaccessible, too often irreversibly so?

I have more questions than answers, obviously. I trust in the multiplicity of the answers to be found, that the way forward will be in expanding my capacity to be with complexity, with the both/and. In the space between reckoning with my colonial past as a white-bodied person living on Turtle Island, and the uncertainty of our climate catastrophe future, I need room for all the nuance and complexity I can muster to hold.

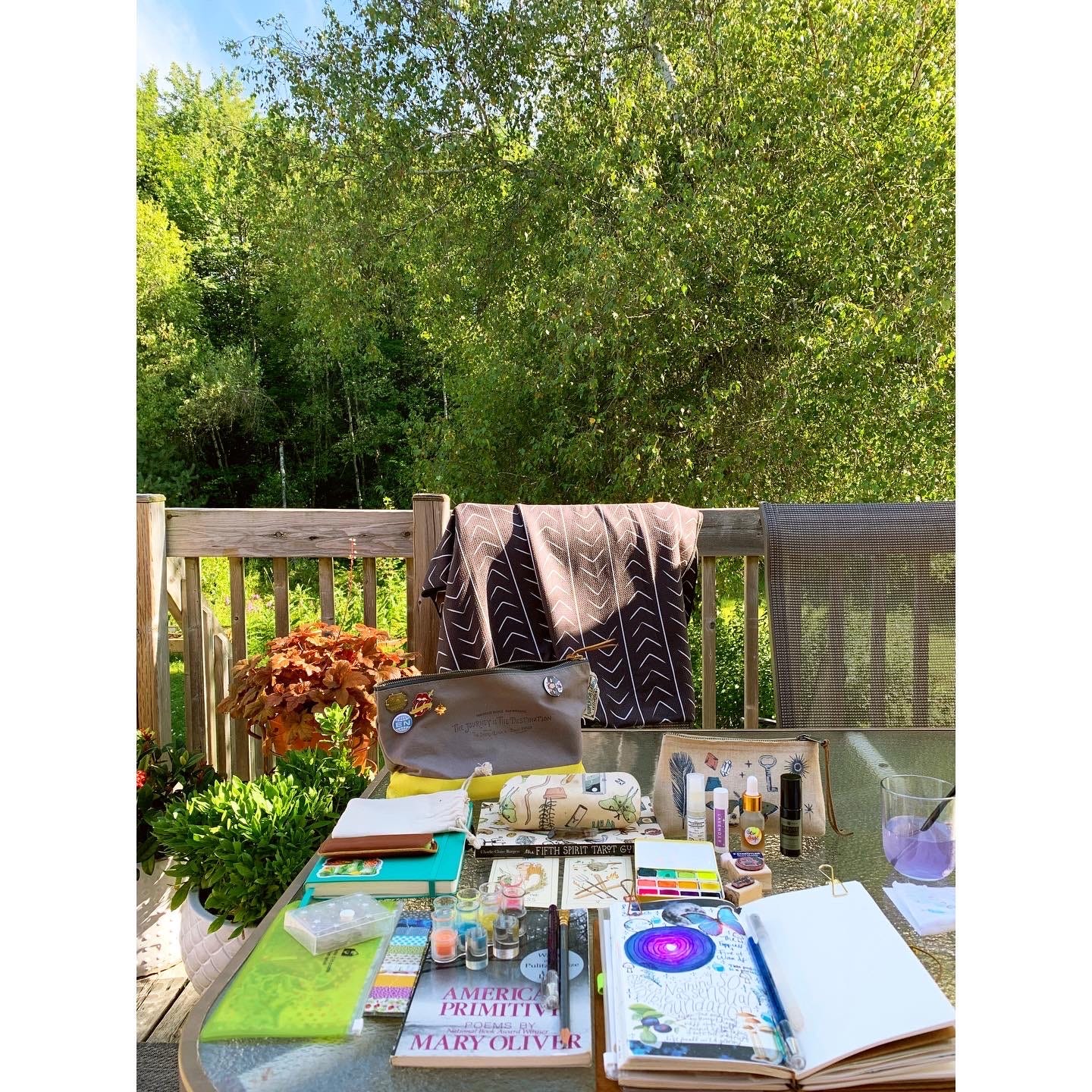

I don’t have a neat bow with which to wrap up this essay. I have grief, and longing, and I know that these too can forge a path, are a way to divine a way forward. I have pressed plants, Queen Anne’s lace and ferns, cedar boughs and willow leaves, folded in the pages of my journal.1 I have the writings of Mary Oliver, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and many other plant witches to offer solace and a vision for what might be possible.

The land knows you, even when you are lost.

-Robin Wall Kimmerer

CURRENTLY RESOURCING WITH: A weekly roundup of shit I’m enjoying.

🌈 I am not kidding when I say that this is the most important item I take with me when I am traveling. Home is where the bidet is.

🌈 I also loved using this collapsible pour-over coffee dripper to make my morning decaf coffee while using other people’s kitchens.

🌈 I bought a Canon Ivy mini photo printer for travel journaling and yes, I can confirm that printing stickers of your travel pictures is as fun as you’d think it is.

🌈 Maggie Rogers’ new album Surrender is epic. This song in particular won’t leave me alone.

🌈 I happened upon this book while browsing in a bookstore (my favorite way to discover new books) and I’m really enjoying it.

🌈 Loved this podcast episode on Kate Bush & the music of Stranger Things.

🌈 Reservation Dogs is back for a second season on Hulu. Stoodis!

Filmed on location in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, Reservation Dogs is a breakthrough in Indigenous representation on television, both in front of and behind the camera. Every writer, director and series regular on the show is Indigenous. This first-of-its-kind creative team tells a story that resonates with them and their lived experiences.

I’m using words from the Canadian national anthem, acknowledging its emotional resonance for me as an expat, while at the same time denouncing the horrors perpetrated by this colonial nation state on the bodies, lives, and culture of Indigenous peoples.

Love and resonate with this so, so much -- right now especially.

Thank you for this piece of writing. Lovely. Just what I needed. xo